The sum of digits of a power of a number

Here’s an interesting question raised by Mark Jason Dominus: consider the fact that

\[7^4 = 2401 \quad \mathrm{ and } \quad 2 + 4 + 0 + 1 = 7\]or that

\[53^7 = 1174711139837 \quad \mathrm{ and } \quad 1+1+7+4+7+1+1+1+3+9+8+3+7 = 53\]First, take a moment to enjoy these pleasing coincidences.

Next, the question: how surprised should we be when such a thing happens, i.e. how likely is such a thing to happen?

It’s easy to try out things like this by writing some code. The following was entered into a Python 3 shell, and simply tries, for each number $N \ge 2$, consecutive powers $N^k$ for $k \ge 1$, looking for those where the sum of digits of $N^k$ is $N$, until $k$ becomes rather large and there are unlikely to be any more such powers.

N = 2

while True:

k = 1

print("%d: " % N, end="")

good = []

while True:

m = N ** k

s = sum(ord(c) - ord('0') for c in str(m))

# print("%d, " % s, end="")

if len(str(m)) > 5 * N: break

if s == N: good.append(k)

k += 1

if good:

print("\n %s" % good)

else:

print("")

N += 1

The first few lines of output:

2:

[1]

3:

[1]

4:

[1]

5:

[1]

6:

[1]

7:

[1, 4]

8:

[1, 3]

9:

[1, 2]

10:

11:

12:

13:

14:

15:

16:

17:

[3]

18:

[3, 6, 7]

(for example, $17^3 = 4913$ and $4 + 9 + 1 + 3 = 17$; similarly for $18^3$, $18^6$ and $18^7$) and the last few at the time I’m writing this:

1641:

1642:

[109]

1643:

1644:

1645:

1646:

1647:

[111, 116]

1648:

[108]

1649:

1650:

1651:

1652:

1653:

1654:

1655:

1656:

[115]

1657:

[120]

1658:

1659:

1660:

1661:

1662:

Here’s one heuristic way to think about this problem.

Let $S(m)$ denote the sum of digits of a number $m$. Consider a number $N^k$. It has about $k \log N$ digits (logarithm to base $10$). Though these digits aren’t “random” (they are completely determined by $N$ and $k$), if we treat each digit as being any one of $0$ to $9$ with equal probability (this is definitely not true of the first or last digits, but becomes a better model for many digits in the middle), then the expected sum of digits would be

\[S(N^k) \approx 4.5k \log N\]That is, for a fixed $N$, each time we increase $k$ by $1$, the digit sum $S(N^k)$ increases by about $4.5 \log N$. We’ll get $S(N^k) = N$ when this sequence, which is (roughly) linearly increasing by about $4.5 \log N$ at a time (and taking on only integer values), hits exactly $N$, as opposed to “missing” it, i.e. going from values below $N$ to above $N$.

This we should expect to happen with “probability” about $\frac{1}{4.5 \log N}$, because in a neighbourhood around $N$ of size $4.5\log N$, we expect about one number to be hit, and for all we know, $N$should be about as likely as any other number.

E.g. for $N$ about $1650$, we should expect to see this for about $1$ in $14$ numbers (or actually a bit more than twice than that; see below). This is roughly in the same order of magnitude compared to what we actually see above ($5$ out of $22$ numbers).

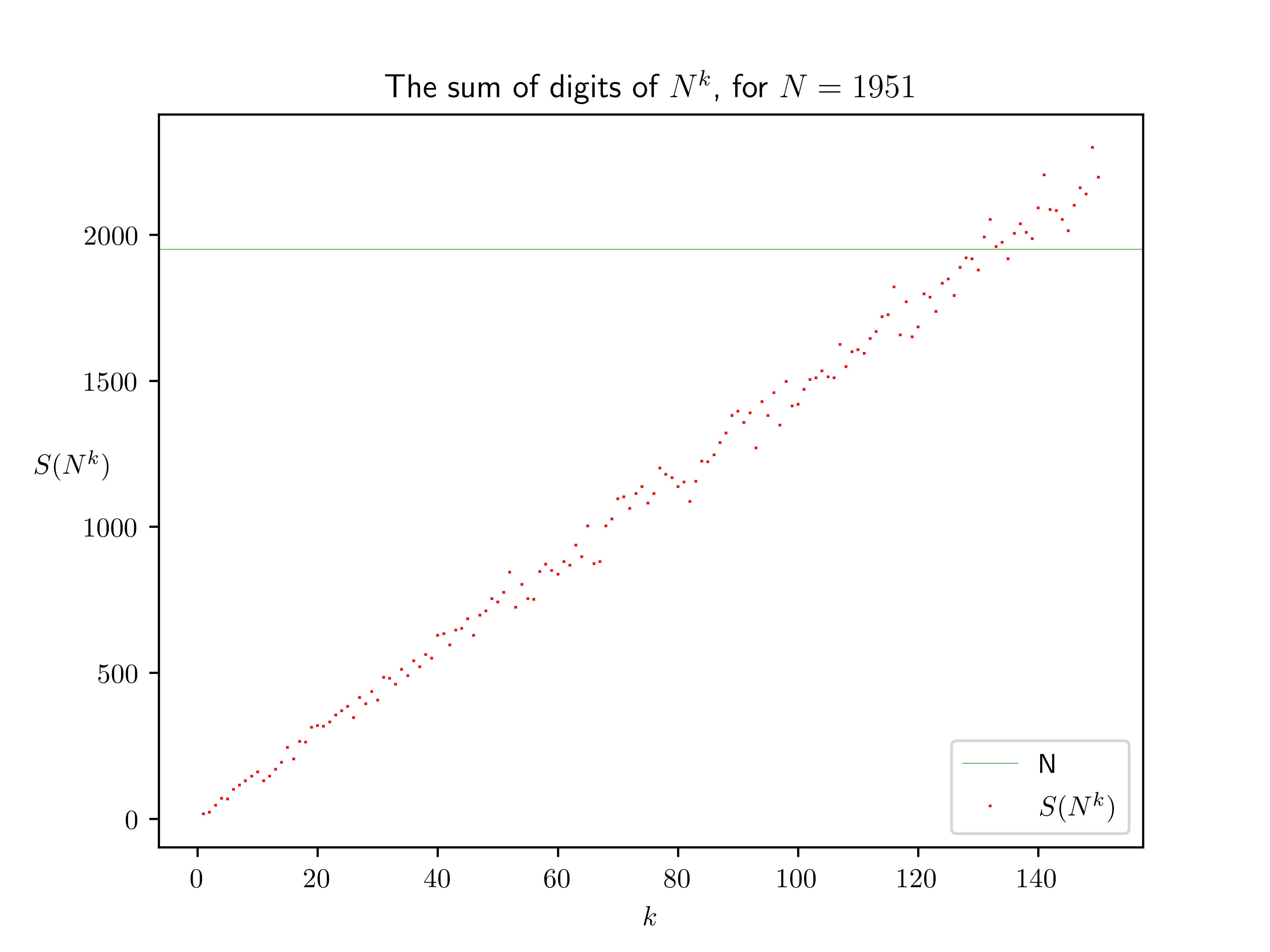

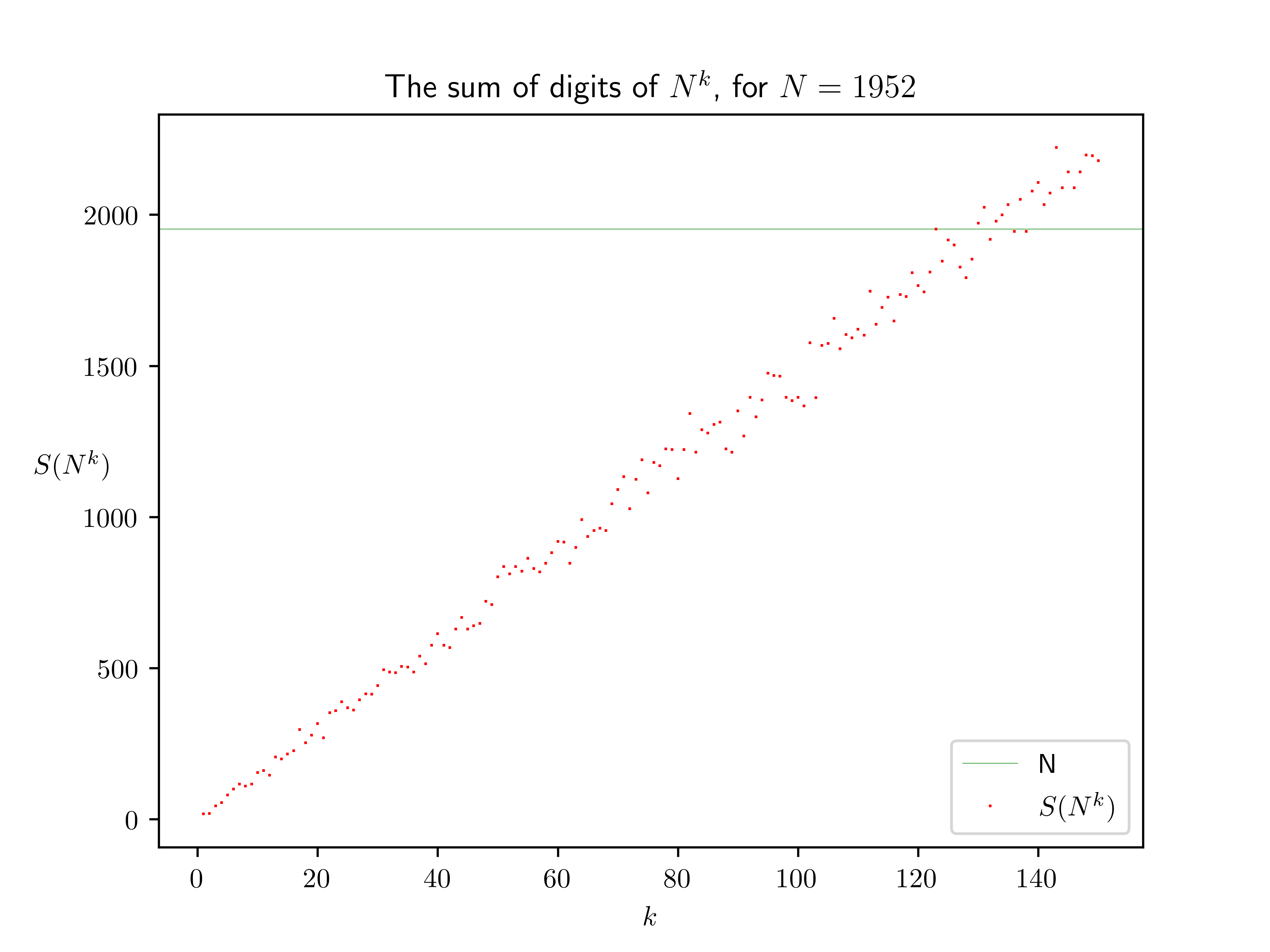

Some pictures may help. Below are plotted $S(N^k)$ versus $k$, for $N = 1951$ and $N = 1952$ (sorry you’ll have to open images at original size and really zoom in to see that $N$ is missed in the first case and hit in the second).

(Above we estimated the “probability that a number $N$ is good”, i.e. has such a power $N^k$, as $1/(4.5 \log N)$, but for some numbers $N$ the “probability” is actually higher: when $N$ is a multiple of $3$ (like $1647$ and $1656$ in the output above), then so is $S(N^k)$, so in the neighborhood only multiples of $3$—including $N$—are going to be hit. Similarly for multiples of $9$. Conversely when $N$ is not a multiple of $3$, we know that $S(N^k)$ will not hit multiples of $3$ in the neighbourhood, i.e. it has only $2/3$rds as many choices. So maybe we should revise our probability $p = 1/(4.5\log N)$ to $\frac19(9p) + \frac29(3p) + \frac69(\frac32p) = \frac83p$. Also, when $N$ is a multiple of $10$, say $N = 10m$, to have $10m = N = S(N^k) = S(10^k m^k) = S(m^k)$ is more likely, as $S(m^k)$ only grows by about $4.5\log m$ at a time instead of $4.5 \log N$ at a time.)

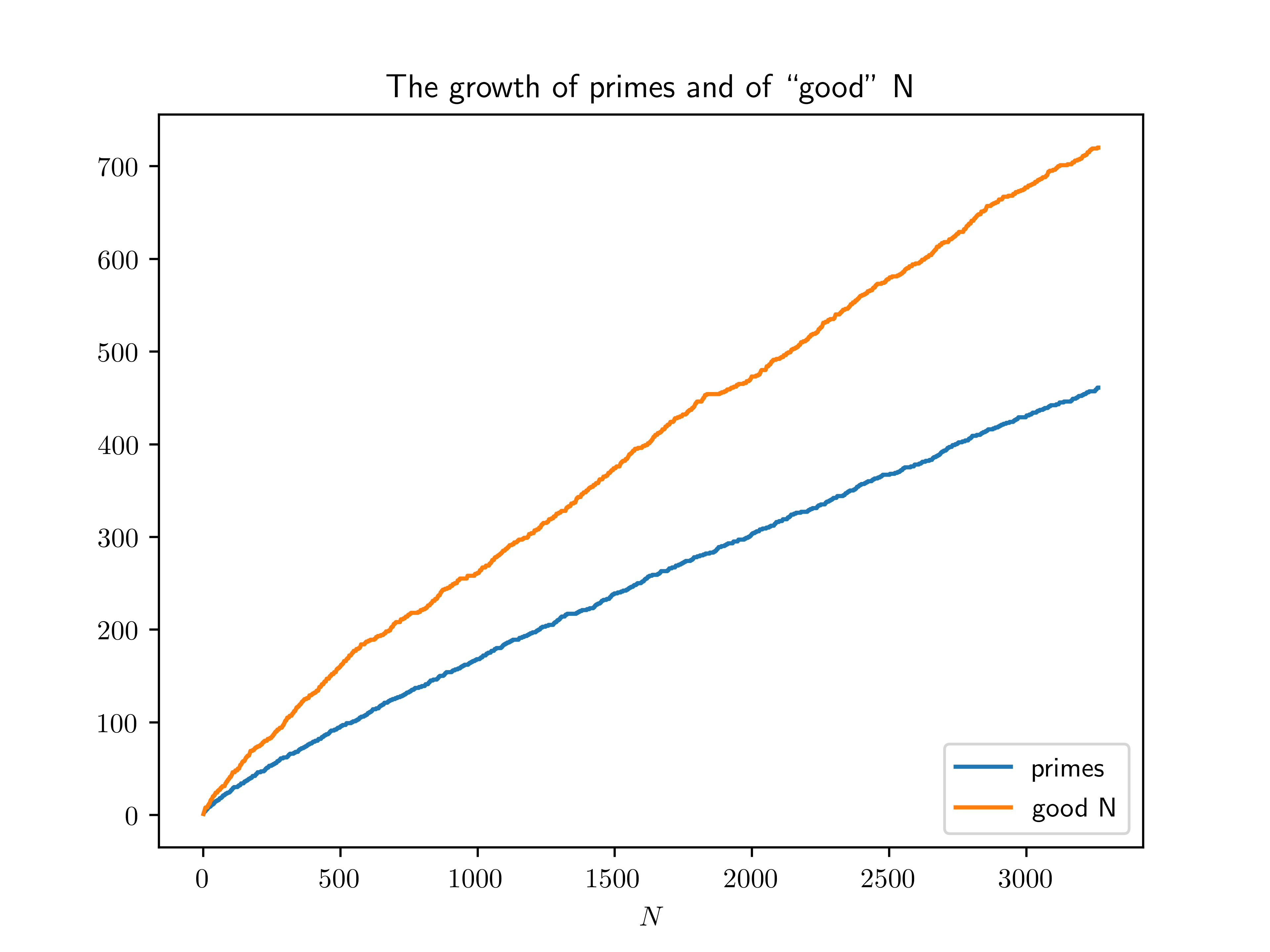

In particular, we expect infinitely many numbers $N$ for which some power $N^k$ satisfies $S(N^k) = N$ (as the sum of the reciprocals of the logarithms diverges), and in fact, I think we can expect the number of such $N$ below a certain threshold $M$ (now I’m wishing I’d used lowercase $N$ so far…) to be of the order of (a bit more than)

\[\sum_{N=2}^{M} \frac{8}{3}\frac{1}{4.5 \log N} \approx \frac{16}{27} \int_{2}^{M} \frac{1}{\log N} = \frac{16}{27} \operatorname{Li}(M)\]where $\operatorname{Li}(M)$ is the logarithmic integral, and this grows like $O(M/\log M)$ – and in fact by a deep theorem (the prime number theorem), this is about the same as the number of prime numbers below $M$, as

\[\pi(x) \sim \operatorname{Li}(x)\]Check: This file contains the output for $N$ up to $3263$, and the growth of the number of “good” $N$ up to each limit can be compared with the growth of the number of primes in that range:

Our crude heuristic seems to have underestimated the true number by a factor of about $2.7$, and it might be interesting to explore why, but otherwise seems to hold up.

(Thanks for reading! If you have any feedback or see anything to correct, contact me or edit this page on GitHub.)